From new gender policies to commitments on living wages, we’ve come a long way since Oxfam published its first supermarkets scorecard in 2018, when retailers lacked the understanding and appetite to do human rights due diligence, says Radhika Sarin. What does the 2022 scorecard reveal – and what more must be done?

“Five kilos of extra beans on each worker’s table,” says Joseraldo Medeiros, a union leader in Brazil’s fruit exporting region of Rio Grande do Norte. “If we hadn’t fought for this, workers would not have received [the equivalent of] five kilos of beans in their salary.”

The five kilos of beans cost 40 reais, or around $8, which is the extra monthly pay workers now receive as a result of a collective bargaining agreement that was struck after Oxfam pressed international supermarkets who buy fruit from the region to back wage negotiations that had stalled. This is an example of how Oxfam’s Behind the Barcodes campaign has called on powerful supermarkets to use their leverage to ensure workers’ rights are respected.

Today, as we launch the fourth scorecard, we want to highlight the areas of improvement helping to change the lives of workers in supermarket supply chains – and spotlight one key area where we think supermarkets need to do much more.

The six supermarkets in the UK scorecard – Asda, Aldi, Lidl, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Tesco – account for over 80% of the UK’s grocery market share.

There's a race to the top taking place

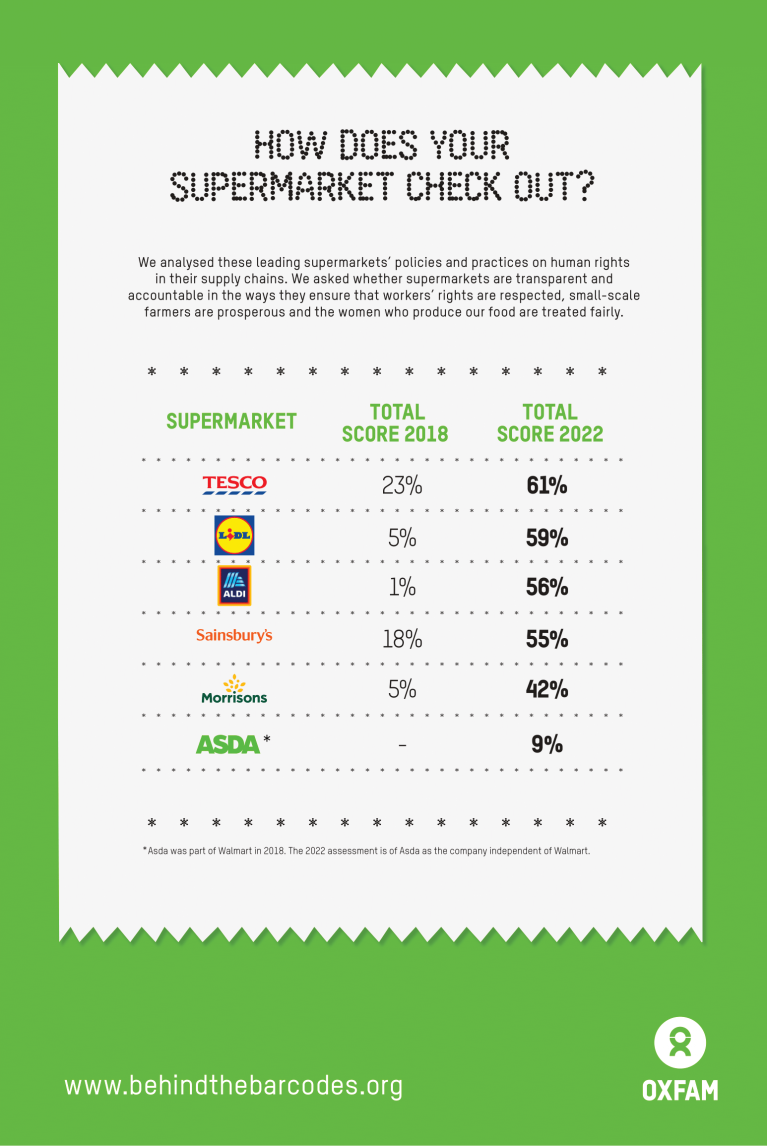

The pressure of the campaign, with Oxfam supporters and supermarket customers calling for change has created a “race to the top” among UK supermarkets to improve their human rights rating. All five supermarkets we rated in 2018 – Aldi, Lidl, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Tesco – have improved their scores.

Initial laggards Aldi and Lidl, the focus of Oxfam campaigns in previous years, have now taken significant steps to adopt a human rights approach and published new policies and commitments. Both companies, for instance, have published several deep dives known as human rights impacts assessments (HRIA) into supply chains rife with risk, such as avocados from Peru and tea from Kenya, in order to understand, identify and address human rights impacts on people.

Tesco published an HRIA of its shrimp supply chain in Vietnam. Following this assessment, it committed to promoting gender equality by working with its suppliers to tackle gender-based violence and sexual harassment in the workplace. Tesco also tackles discrimination by setting time-bound targets for increasing the number of women in supervisory and management roles across all its direct food suppliers.

This year is the first time we have assessed Asda as an independent company. It was owned by US firm Walmart until last year. Asda’s low scores demonstrate that it urgently needs to prioritise putting a human rights strategy in place to catch up.

As well as the UK tables above, we have produced ratings for other European supermarkets this year, many of whom have also improved their scores as a result of our campaign. The US supermarkets, which have been significant laggards in past ratings, were not assessed by Oxfam this year. Later this week, Oxfam will be publishing a report with a set of urgent actions US companies need to take to step up and tackle workers’ rights in their supply chains.

In 2020, Oxfam campaigners dressed as giant fruit and veg handed in a petition with 20,000 signatures at Lidl’s London head office, urging the supermarket to do more to protect the workers behind its food (Picture: Rebecca Lonsdale/Oxfam)

Supermarkets are lifting the lid about who produces our food

The 2022 scores also reflect a radical shift in supply chain transparency. In 2018, no supermarket published information about its food suppliers; today, Morrisons, Sainsbury’s and Tesco publish all of their “tier one” (direct) suppliers, an important first step in supply chain transparency as these major supermarkets have thousands of business relationships even at this first level.

Lidl has gone further with its transparency for some products: it now publishes its full chain, from tier one down to the level of the producer, for bananas, tea, strawberries and seafood. Outside the UK, supermarkets such as Jumbo, Albert Heijn and Plus in the Netherlands, have also made strides in supply chain transparency. You can read more about the progress of European supermarkets here.

Gender equality is firmly on the agenda

When Oxfam began campaigning in 2018, almost all supermarkets were “gender-blind” in their policies and approaches, neglecting the specific needs and challenges faced by women such as gender-based violence at work, or the burden of unpaid care and domestic work. Today, there are welcome signs that this is changing, with increasing awareness of the barriers to fair and equal treatment for women workers and producers and a range of commitments by supermarkets to tackle them.

Tesco is the clear front-runner on gender equality, with a score of 76% in this pillar of the scorecard (see below) and a comprehensive gender strategy in place. Tesco’s ground-breaking agreement with the global federation of trade unions, IUF, focuses on access to gender-sensitive “grievance mechanisms” – the process workers use to raise issues, complaints and concerns about things that negatively affect them at work – and on increasing women’s voices and representation in the workplace. Tesco is the only supermarket in the scorecard that has started disclosing detailed data on women for some of its supply chains down to farm level.

Improvements in the scores on gender equality show increasing awareness and action among supermarkets on the barriers to fair and equal treatment for women workers

Sainsbury’s and Lidl, who both now score 48% in the women pillar, are committed to increasing their sourcing from women farmers. They and Tesco are also supporting suppliers to address the root causes of gender inequality. This means, for example, supporting suppliers to ensure women have a voice and can participate effectively in trade unions or farmer cooperatives. Supermarkets must now build on these efforts to tackle the devastating impact the Covid-19 pandemic has had in worsening gender inequalities.

But the drive to cut costs and maximise profits remains a major barrier to better pay and conditions

Oxfam’s 2018 report which launched the Behind the Barcodes campaign highlighted how supermarkets were increasingly squeezing the price they paid their suppliers with less and less of the price at the till reaching the workers and farmers who produce our food. When supermarkets insist on lower prices from suppliers, this has a knock-on effect on working conditions and pay in supply chains.

If supermarkets are serious about human rights, they need to ensure a decent wage for every worker in their supply chain. They should make living wages a non-negotiable cost they are ready to bear when negotiating on prices with suppliers. It is through such progressive purchasing practices that businesses will have the most profound impact on workers.

Some recent moves to tackle low wages are promising, such as Aldi and Lidl participating in the German Living Wage and Income Initiative. Tesco is embedding a living wage commitment into its purchasing practice in the banana sector by financially contributing to fill living wage gaps at its banana suppliers, and by committing to reward suppliers who progress in this area with increased business.

However, there is still much to do: four years on, all supermarkets are still largely failing to demonstrate changes in buying practices that would deliver on their human rights commitments. The handful of good examples so far urgently need to be expanded to ambitious action on purchasing across all high-risk food supply chains. We need supermarkets to switch to responsible buying practices and governments to strengthen legislation that protects workers, including on mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence.

The stark injustices hidden behind the food people throw into their trolleys every day across the UK spurred the launch of Behind the Barcodes. Four years later, Oxfam is proud that our supporters’ campaigning has driven a real shift in supermarkets’ attitudes and actions – and we’ll keep on working to challenge the barriers to a decent life for the millions who produce our food.

This article was first published on Oxfam's Views and Voices blog.