My early memories of establishing the ETI Secretariat in 1998, are the barrage of questions from concerned consumers, media, and investors. “Which is the most ethical clothing brand? What do you know about dormitory conditions in China? Where can I buy a pair of ethical socks”?

Trade unions and NGOs had mobilised public opinion, to demand greater corporate accountability for workers in their supply chains. In the dialogue that followed, the founding members conceived the idea of ETI as a response to address these concerns.

ETI provided a creative and safe space for business, trade unions, and NGOs to develop the concept of human rights due diligence.

ETI emerged as a bold, new idea in alignment with the "third way" policy environment of the New Labour Government, which had recently established the Department for International Development. It provided a creative and safe space for business, trade unions, and NGOs to develop the concept of human rights due diligence. Recognising that corporate codes of conduct could have varying outcomes for workers, ETI aimed to define and promote business practices that delivered positive results, especially for the most vulnerable in the supply chain.

Those were exciting times. ETI found itself at the forefront of a novel approach to business and development, operating under intense public, media, political, and academic scrutiny. The organisation pursued an ambitious learning agenda, supporting members and their partners in collaborative projects to generate new knowledge and techniques. Simultaneously, ETI focused on building an effective organisation with the appropriate governance, structure, and culture for risk taking, collaboration and decision-making.

Similar initiatives emerged in North America and Europe, often opting for business verification or auditor certification strategies. In contrast, ETI remained committed to continuous learning and improvement.

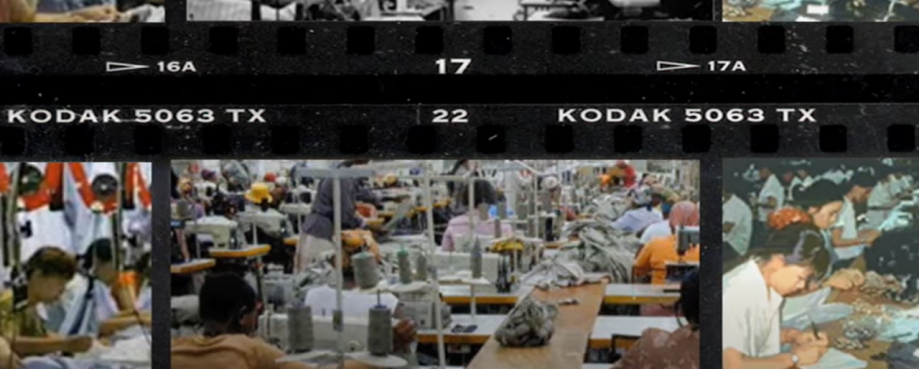

Meeting the needs of a rapidly expanding membership posed an immediate challenge for ETI. Members were eager to engage in new collaborative projects that aligned with their distinct priorities and requirements. ETI's greatest strength lies in its unique multi-stakeholder membership, which proved invaluable in developing inclusive social audit techniques across various industries. The organisation's focus naturally gravitated toward safeguarding the most vulnerable workers in the supply chain, including homeworkers, migrant and seasonal workers, and women in the informal economy.

Around the same time, similar initiatives emerged in North America and Europe, often opting for business verification or auditor certification strategies. In contrast, ETI remained committed to continuous learning and improvement. Although it was challenging to communicate this approach in a world seeking definitive answers to ethical challenges, ETI's mission had significant advantages for its time. Recognising the limitations of corporate codes of conduct enabled the development of policies and guidance based on evidence and shared experience. When NGOs, trade unions, and businesses reached consensus, the resulting guidance proved credible, durable, and influential in shaping business practices.

The emerging due diligence regulations of today are built upon the foundations of good practices developed during that time.

ETI was influential in advising the London Olympic Committee, leaving a lasting ethical procurement legacy for the Olympic movement. I recall the long conversations with Professor John Ruggie and his team during the consultations that ultimately led to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The emerging due diligence regulations of today are built upon the foundations of good practices developed during that time.

By the early to mid-2000s, the impact of ETI became evident. Its inclusive approach, involving trade unions, NGOs, and businesses to build knowledge and capacity within supply chains, started yielding results. For instance, ETI's pilot project with the South African wine industry contributed to the establishment of the Wine Industry Ethical Trade Association, which continues its mission to this day. ETI played a pivotal role in the formation of the Gangmasters Licensing Authority in 2005 and joined its first board. Prior to the Morecambe Bay cockling tragedy that claimed the lives of 21 migrant workers, ETI's Seasonal and Migrant Workers Group united the food industry, laying the groundwork for regulations that supported the design of a private member's bill.