As the dust settles on a disappointing and at times fractious COP29, where so-called ‘developed’ nations failed to face up to their historical role as the world’s major emitters, ETI reflects on the increasing saliency of extreme heat as a human rights risk for workers in global supply chains.

2024 “a masterclass in climate destruction”

Once again the UN’s Secretary General Antonio Guterres, did not mince his words:

2024, with the hottest day on record, and the hottest month on record. This is almost certain to be the hottest year on record, and a masterclass in climate destruction.

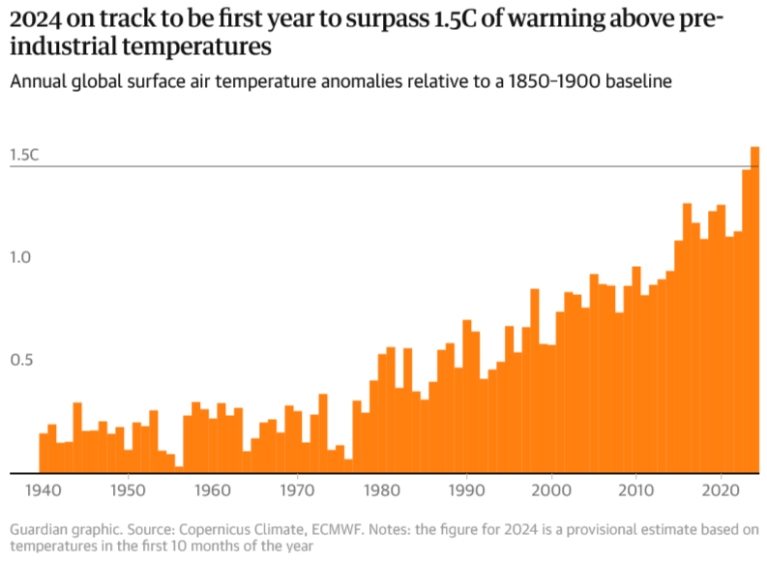

Data released by the EU’s Copernicus Climate Service, and reported in The Guardian, shows that 2024 is “virtually certain” to be the hottest year on record and the first where average surface temperatures have surpassed 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming.

Courtesy of Guardian News & Media Ltd.

In his opening address to world leaders at COP29 in Baku, Guterres described multiple climate disasters that are occurring with increasing frequency, including workers “collapsing in insufferable heat.”

At times, a fractious climate conference.

Extreme heat and the world of work

Earlier in 2024, the ILO launched, Ensuring safety and health at work in a changing climate. The report asserts that 70% of workers globally face climate change-related health risks, and more than 2.4 billion people are likely to be exposed to excessive heat whilst at work. Data published in The Lancet reports 490 billion potential hours of labour were lost due to heat exposure in 2022, a 42% increase on the period 1991-2000. These are frighteningly large numbers. It’s clear that extreme heat is a human rights risk for workers that is rapidly growing in saliency. It’s against this backdrop that ETI convened members and non-members for a webinar on extreme heat.

Oppressive heat in workplaces in Cambodia

Dr Laurie Parsons and Dr Pratik Mishra of Royal Holloway, University of London presented their research from Cambodia. Data from internal body temperature monitors worn by 788 workers shows the proportion of working time spent at unsafe core body temperatures (38 degrees C and higher). The findings are incredibly detailed and include results for workers across apparel, transportation and informal food selling, and the differences between different roles within these sectors. For example, in apparel, workers in the ironing section spend three times as much time at unsafe temperatures as their colleagues working at sewing machines.

Crucially the research also explores which actions are most effective at reducing workers exposure to unsafe temperatures. They find that individual actions are less effective than collective actions. More specifically, union members spent 51% less time at unsafe core temperatures, and workers in unions that negotiate with employers on heat mitigation actions experienced 74% fewer minutes at unsafe temperatures than those that didn’t. This is powerful data that confirms what we already know: freedom of association and collective bargaining are fundamental rights and they are enabling rights – they enable other rights, such as the right to safe and hygienic working conditions, to be exercised.

Empowering workers and protecting the planet in Ghana

These themes were further explored by Pauline Watine from Ethical Apparel Africa. Pauline explained the huge potential of apparel manufacturing in West Africa, given the region’s long history in textiles, but also crucially the export industry’s opportunity to “get it right from the beginning” – with decent work and environmental sustainability integrated from the outset. This is exactly what Ethical Apparel Africa (EAA) is doing at its manufacturing facility in Ghana, which provides well-paid skilled jobs to 500 workers.

But EAA’s workforce is not immune from rising global temperatures. Last year they experienced 50 days above 35 degrees Celsius, up from 45 days the year before. In response, Pauline described how EAA has invested in solar panels on the factory roof. These help keep workers at safe temperatures, powering an air circulation system in the main building and air conditioning units in the ‘worker wellbeing centre’. The technologies are complemented by the extensive greenery around the factory which also reduces air temperatures. Hydration stations provide easy access to cool drinking water and a health screening programme enables EAA to identify workers most at risk from heat-related illness due to underlying health conditions. Vulnerable workers are assigned to production lines in cooler areas and allocated less physically demanding tasks.

But underpinning all the heat mitigation actions at EAA is a collaborative organisational culture, where workers are represented by worker committees at three levels: shop-floor workers, middle and senior managers. Committee members are democratically elected and supported with training to fulfil their roles effectively. Committees meet regularly with company directors to discuss staff concerns and to collaborate on solutions. Addressing the impacts of rising temperatures has been high on the agenda.

Interestingly, when questioned by a participant about the prevalent culture of short lead times and high production targets within the apparel industry, Pauline’s response again emphasised the importance of collaboration. Not only does EAA review production schedules and order deadlines with key members of its workforce, but it also aims for a more collaborative approach with supply chain partners. EAA discusses with its customers how production schedules are managed, what is possible, what is not feasible, and the potential impacts that unrealistic deadlines would have on the workforce.

Learning from the wider trade union movement

Steve Craig, ETI’s Trade Union Coordinator and National Development Coordinator at Unite the Union shared experiences from the wider trade union movement on tackling extreme heat. Heat related occupational safety and health risks include heat exhaustion and heat stroke, which can be fatal if not identified and treated rapidly. But we also know that workplace accidents increase as temperatures rise. Research from ETUC, shows that as temperatures exceed 30 degrees Celsius, the risk of work accidents increases by 5 to 7 percent. When temperatures surpass 38 degrees, the risk increases by 10 to 15 per cent. These are big increases with potentially life-threatening impacts on workers.

Workers in the construction industry have been particularly active on heat risk. Building and Woodworkers International have worked with their affiliates to launch a manifesto, call to action and awareness raising material for both workers and employers on this critical issue. This is an approach that other sectors can learn from, adapt and replicate. As always, Steve got to the heart of topic very eloquently, and – reinforcing key messages from the Oppressive Heat research in Cambodia and Ethical Apparel Africa’s experience in Ghana – stated: “this is about workers as rights holders, trade unions as stakeholders – it’s not about shareholders - as we are all shareholders in the planet.”

Key takeaways

It’s always challenging and often risky to attempt to distil key messages from such detailed and nuanced presentations and discussion. However, these four came through consistently from our panellists.

- To mitigate the impacts of extreme heat on workers, we need to better understand these impacts.

- Businesses are already taking action: let’s learn from existing good practices.

- Workers and their representatives are rights-holders and they have valuable knowledge and expertise. Work with them.

- Collaborate! With supply chain partners, with workers and their representatives, with researchers. No-one can effectively address this challenge on their own.

You can find the webinar recording and slides here. For non-ETI members we have published this Snapshot that aims to explain how periods of extreme heat increase risks for workers. This is a summary of an extended briefing available to ETI members. As the planet continues to warm, extreme heat presents a human rights risk for workers that is rapidly growing in saliency. However, as our webinar illustrates, knowledge, experience and expertise on how to mitigate this risk already exist. It’s incumbent upon us to rapidly deploy this to ensure workplaces and workers are safe as our planet continues to warm.