Earlier this year Erinch Sahan, Business and Enterprise Lead at the Doughnut Economics Action Lab joined ETI’s just transitions working group to discuss planetary boundaries, social justice and business design. This blog explores some of the key insights and questions raised.

Planetary crisis

Is ours the era of crisis? With 2024 confirmed as the hottest year since the pre-industrial age, and 2025 opening with wildfires tearing through Los Angeles, there’s no doubt climate crisis is upon us. But scientists are also warning of a biodiversity crisis, with species disappearing ten to 1,000 times faster than normal, and a plastic pollution crisis with 12 million tonnes of plastic dumped in oceans annually. The UN now refers to this as the ‘Triple Planetary Crisis’.

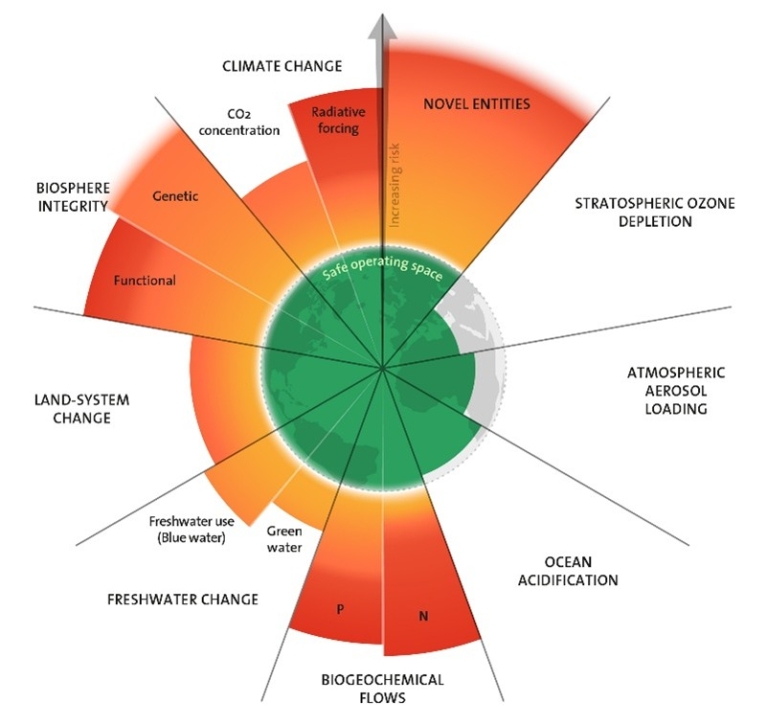

Analysis by earth systems scientists, including Johann Rockström at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, paints a grim picture. Their latest report reveals that human activity has pushed six of the nine planetary boundaries beyond their safe limits, risking, “large-scale abrupt and irreversible environmental changes.” The scientists explain that the boundaries comprise an interconnected system: “We cannot consider Planetary Boundaries in isolation in any decision making on sustainability. Only by respecting all nine boundaries can we maintain the safe operating space for human civilization.”

The 2023 update to the Planetary boundaries. Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Credit: "Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, based on analysis in Richardson et al 2023".

Where do people fit in?

Human activity is driving these crises, but surely, it’s neither feasible nor desirable to halt all modern economic activity and revert to some pre-industrial idyll?

That being said, the benefits of today’s modern global economy are unevenly distributed. Today, one quarter of the way through the 21st century, around 700 million people go to bed hungry, 2.2 billion lack access to safe drinking water, and 4.5 billion lack access to essential healthcare services [Source: SDG Progress Report 2024]. A small but significant proportion of the global population are pushing the earth’s systems towards disaster, whilst others struggle to meet basic needs and will suffer most acutely from the multiple interconnected crises unleashed by the rest of us.

Enter the doughnut!

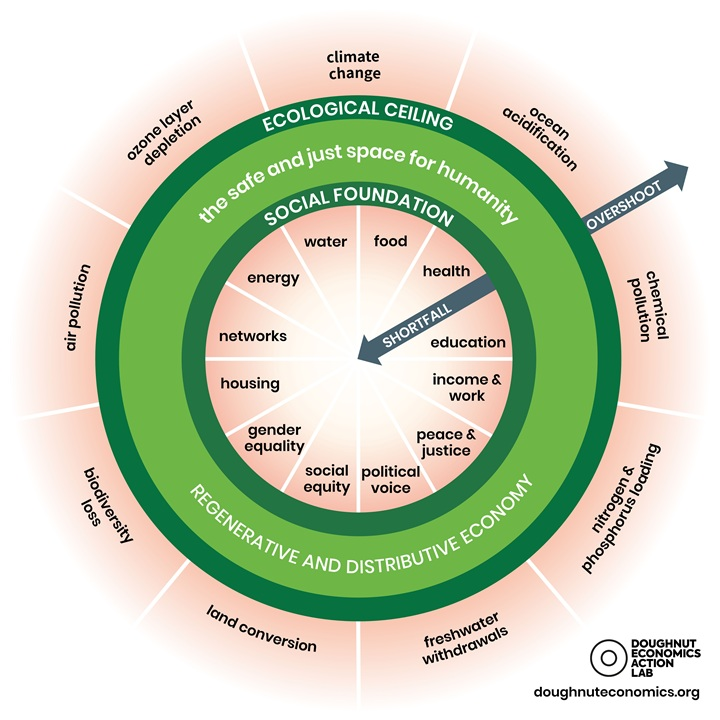

Doughnut Economics provides a framework that integrates planetary boundaries with human needs, as outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Developed by Kate Raworth during her time at ETI member NGO Oxfam GB, and brilliantly elucidated in her bestselling book, Doughnut Economics is inspiring a new generation of activists, policymakers, entrepreneurs and educators to rethink economic systems for the 21st century.

The Doughnut couples the nine planetary boundaries with a social foundation, generating a ring shaped, or doughnut shaped, framework. It prompts us to consider both the biophysical limits to human activity and the right of all people to live free from deprivation. The brilliant thinkers – and doers – at Doughnut Economics Action Lab recognise that businesses have a role to play providing the goods and services that people need and want, but challenge us to redesign business in two fundamental ways. They identify the current linear ‘take-make-use-dispose’ model of production and consumption as inherently wasteful and at odds with the cycles of the natural world and planetary boundaries. Instead, they focus their energies on identifying, celebrating and promoting regenerative circular models. At the same time, they identify that currently the fruits of enterprise are retained by too few individuals, with growing income and asset inequality leading to polarisation and worse; hence their focus on distributed ownership and governance to combat growing inequality.

The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries. Image credit: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0.

Implications for ETI

Models of distributed ownership and governance are represented in ETI membership, notably by the John Lewis Partnership and the Co-op . Many members are beginning to take steps towards circularity through take-back and repair schemes, such those at River Island, Very Group and Selfridges. Bantam Materials' Prevented Ocean Plastic is perhaps a more ambitious example of a circular supply chain. Notwithstanding these important examples, what could Doughnut Economics mean for ETI’s work more broadly?

Just Transitions and doughnuts

Just transitions are central to ETI’s current strategy. Referenced in the Preamble to the Paris Climate Agreement, and with an ILO-led work programme initiated at COP28, just transitions is often most closely associated with climate action. However, links between climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution are widely understood. Perhaps Doughnut Economics provides a powerful framework to address these issues within the context of just transitions, alongside other key ecological and biophysical issues like freshwater use, ozone depletion, and the proliferation of PFAs or ‘forever chemicals’ for example.

The urgent need to develop and scale technical solutions can sometimes overshadow the justice aspect of just transitions, which is crucial. It’s not simply a transition we need, it must be a just transition. The trade union movement has played a central role in developing and advocating for this, focusing first and foremost on workers’ rights, which is especially critical in light of increasing restrictions on workers’ right to organise. However, human rights due diligence challenges us to take a broader perspective and consider not only the human rights impacts on workers, but also on wider affected communities, such as people living near workplaces, or across the wider watershed for example. Doughnut Economics reinforces this broader perspective, by incorporating the social foundation – providing a helpful reminder and structure.

From transition to transformation

Doughnut Economics can help broaden our perspectives on the interconnected changes needed. Its dual focus on shifting from a) linear to circular supply chains and operations, and b) concentrated to distributed ownership and governance, are potentially radical. At first glance these may feel more like transformations than transitions, but examples documented by the Doughnut Economics Action Lab, and others mentioned within ETI membership, demonstrate where change is already being made. Given the gravity of the planetary crisis, such radical alternatives are sorely needed.

We must also recognise the frameworks we already work with are radical in their own right. The ETI Base Code, grounded in ILO conventions, has existed for over 20 years, yet, workers around the globe still lack basic rights. Freedom of association and collective bargaining (Base Code clause 2) are enabling rights, and central to social dialogue, which is fundamental to just transitions. Social dialogue enables workers to participate in decision-making and contribute invaluable solutions in processes of change. In many workplaces this perspective itself presents a radical change.

World Day of Social Justice 2025

Social justice is at the heart of just transitions. The work of Johann Rockström and colleagues, Kate Raworth, Erinch Sahan and their wider team challenge us to refine our understanding of just transitions. Their insights expand our understanding of interconnected planetary crises, and support us to a take broad perspective of rights-holders and the economic, social and cultural human rights, which alongside labour rights, must be respected. Finally, it begins to challenge us to consider how businesses and supply chains that align with a ‘just’ future might look like. Understanding the foundation that social dialogue with workers provides for these processes of transition will be key. This is a very initial exploratory discussion, but reflecting on World Day of Social Justice 2025, when the theme was “strengthening a just transition for a sustainable future” we hope it provides some food for thought.