On the third anniversary of the horrific attack on a woman medical student in Delhi, what is being done about sexual harassment in the workplace?

While I am posting Christmas cards and decorating the Christmas tree, my friends in Delhi are today marking Nirbhaya Chetana Divas.

That need translating. It’s the Memorial Day for Jyoti Singh, the 23-year-old student who was raped and murdered on a Delhi bus three years ago today. Nirbhaya means “fearless”.

The normally comatose Indian government came under huge public pressure as a result of the case, so took several steps - including finally passing a law on sexual harassment at work. I blogged about it at the time.

India is not the only country with a law on sexual harassment at work, and I’ll come back to legislation in the moment. The real issue is accepting that there is a problem in the first place. Conventional social audit techniques do not provide anything like the real picture. Let me illustrate how difficult it is to get people to talk about sexual harassment with another story from India.

Five years ago I wrote a manual about HIV/AIDS in the workplace, which we were field testing in Delhi at a national workshop run in conjunction with Indian Railways. Half the participants were nominated by the railway trade unions, and half from Indian Railways’ own extensive medical network.

It was a great workshop; after the first morning I forgot who were from the trade unions and who were from the employer, which I take as a good sign.

Suddenly, with just a couple of hours to go on the third day, somebody began talking about sexual harassment. On Indian Railways, it happens like this: when a male employee dies, a family member is given a job. In many cases it is the widow and it seems that they are often given jobs at a remote location, where they may be working on their own and managers know where they can be found. Such women workers are targeted.

Once somebody had mentioned the problem, the logjam broke and it emerged that although Indian Railways has got excellent policies, the male manager perpetrators were getting away with harassing these isolated female employees.

Now, all the women on the workshop were feisty, well-educated and had been very vocal for more than two days of the workshop. And this was a workshop where we had created a safe space to talk about sex and relationships - you can’t really avoid that if you’re talking about HIV/AIDS. But it had taken two days for somebody to speak up about what apparently was a well-known problem.

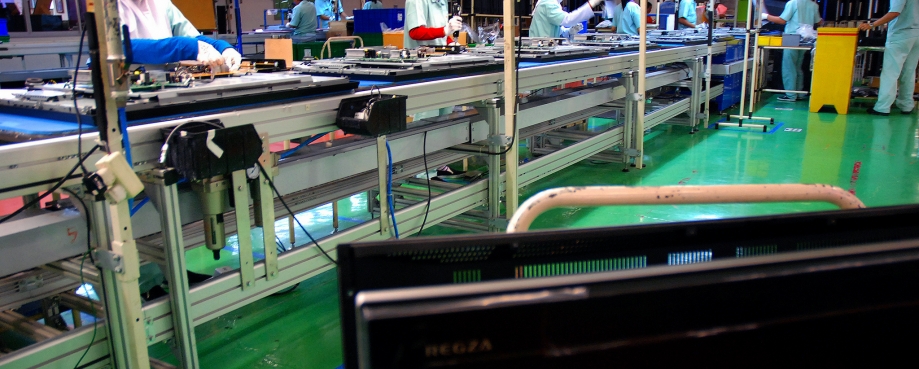

Imagine then, how likely is it that a sewing machine operator will open up to an auditor about being harassed? At a garment factory without even the good policies that Indian Railways had in place?

But we do have some data on how many women workers experience sexual harassment.

- A report by the NGO Women Working Worldwide, which is an ETI member, found that on Kenyan flower farms, 86% of workers had witnessed sexual harassment in one form or the other. More than 60% of the cases were perpetrated by male supervisors over women workers. In return for submitting to sexual advances, women workers were usually offered permanent employment, promotion or transfer to an easier job or threatened with non-renewal of their contracts.

- In Bangladesh, 68% of women garment workers in one survey reported verbal harassment, including being asked for sex

- In Nepal, 54% of women workers reported that they had experienced sexual harassment in their workplace

- In Indonesia, more than 80% of female employees reported that they were concerned about sexual harassment

- In China, the figure is 20%

- In the UK, six in ten working women have had a male colleague behave ‘inappropriately’ towards them

Do I need to go on? Ask nicely and I will send you the references.

These studies take place away from the workplace, where women workers have the space to talk about the problem, usually in terms of “such and such a thing happened to a friend of mine”. Women rarely describe sexual harassment as happening to themselves, because the sense of shame is so acute.

What about the law?

Having established the scale of the problem, let’s go back and look at the law.

Pakistan and Bangladesh have very similar laws to the act passed in India in 2013. A key feature of these three laws is the establishment of a Sexual Harassment Complaints Committee in the workplace.

If you have read any of my blogs about Bangladesh, you won’t be surprised to learn that there are precisely zero such committees in Bangladesh garment factories.

There are also laws, in some cases “soft laws” in the form of codes, in for example: Costa Rica, Kenya, South Africa, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam. Surprisingly, the ILO does not seem to keep a central database.

So, in many sourcing countries there is a law. That is the starting point. British companies sourcing from those countries should be looking for evidence that their suppliers are complying with the law, just like we look for evidence that they are complying with the law on hours of work, or child labour or minimum wages.

This is not going to “solve” the problem. It is going to at least start to give the message that we take the problem seriously. And as most laws seem to provide for education, it is just possible that some women workers might be able to use that space to start taking action.